Tight monetary policy is not the source of our problems. Monetary policy is loose by any measure. - John CochraneLoose by any measure? Label me skeptical.

Since the unemployment rate reached 6.5% in October 2008, the CPI and the PCE (Bernanke's preferred target) have averaged 1.3% annualized. This number is well below even the Federal Reserve's official target (a better name would be ceiling). Meanwhile, inflation expectations are also well below 2% over the next 30 years! Quite clearly by this measure, monetary policy is not loose.

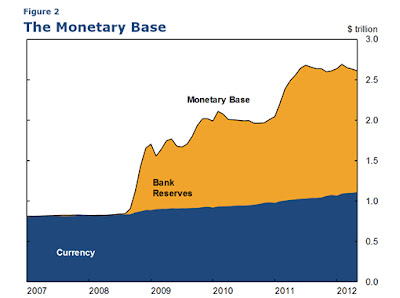

The next measure of policy, the monetary base does show an incredible amount of expansion.

But by charging interest on reserves, the large expansion of the base money

supply is being treated as an interest earning asset and parked at the Federal

Reserve. It would be difficult for Cochrane to call the modest boost in

currency over the past 5 years as easy monetary policy.

David Laidler: Many commentators are claiming that, in Japan, with short interest rates essentially at zero, monetary policy is as expansionary as it can get, but has had no stimulative effect on the economy. Do you have a view on this issue?

Milton Friedman: Yes, indeed. As far as Japan is concerned, the situation is very clear. And it’s a good example. I’m glad you brought it up, because it shows how unreliable interest rates can be as an indicator of appropriate monetary policy.

During the 1970s, you had the bubble period. Monetary growth was very high. There was a so-called speculative bubble in the stock market. In 1989, the Bank of Japan stepped on the brakes very hard and brought money supply down to negative rates for a while. The stock market broke. The economy went into a recession, and it’s been in a state of quasi recession ever since. Monetary growth has been too low. Now, the Bank of Japan’s argument is, “Oh well, we’ve got the interest rate down to zero; what more can we do?”

It’s very simple. They can buy long-term government securities, and they can keep buying them and providing high-powered money until the high powered money starts getting the economy in an expansion. What Japan needs is a more expansive domestic monetary policy.

The Japanese bank has supposedly had, until very recently, a zero interest rate policy. Yet that zero interest rate policy was evidence of an extremely tight monetary policy. Essentially, you had deflation. The real interest rate was positive; it was not negative. What you needed in Japan was more liquidity.

So, loose monetary policy by any measure? Inflation has been persistently below target, expectations of inflation are below target, broad monetary expansion has been neutralized by paying interest on reserves, and low interest rate environment is a symptom of tight monetary policy much like Japan since the early 90's. Cochrane must have a

different definition of loose.