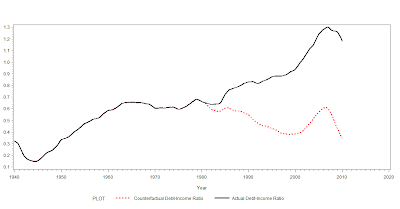

The debt-disinflation of the great moderation:

The 1980s, in particular, were a kind of slow-motion debt-deflation, or debt-disinflation; the entire growth in debt relative to earlier periods (17 percent of household income, compared with just 3 percent in the 1970s) is due to the slower growth in nominal income as a result of falling inflation. In other words, there is no reason to think that aggregate household borrowing behavior changed after 1980; indeed households rescued their borrowing in the face of higher interest rates just as one would expect rational agents to. The problem is that they didn’t, or couldn’t, reduce borrowing fast enough to make up for the fact that after the Volcker disinflation, leverage was no longer being eroded by rising prices. In this respect, the rise in debt-income ratios in the 1980s is parallel to that of 1929-1931.

Figure 2:

Think of it this way: If you borrow money and your income in dollars rises by 10 percent a year (3 percent real growth, say, and 7 percent inflation) then you will find it much easier to pay off the debt when it comes due. But if you borrow the same amount and your dollar income turns out to rise at only 4 percent a year (the same real growth but only 1 percent inflation) then the payment, when it comes due, will be a larger fraction of your income. That, not increased household spending, is why debt ratios rose in the 1980s.

Neither the 1980s nor the 1990s saw an increase in new household borrowing — on the contrary, the household sector in the aggregate showed a primary surplus in these decades, in contrast with the primary deficits of the postwar decades. So both the conservative theory explaining increased household borrowing in terms of shorter time horizons and a general lack of self-control, and the liberal theory explaining it in terms of efforts by those further down the income ladder to maintain consumption standards in the face of a falling share of income, need some rethinking.

Matthew Yglesias correctly points out that we can't blame debt for the Eurozone's recession:

It would be an unpleasant situation. But you would by no means deliberately set about to make yourself unemployed. And yet that's a recession. It's the opposite of taking painful measures to increase output. It's the reverse of pulling more people into the paid labor force. "Don't get deep into debt, or you might be forced to stop working altogether in the future" doesn't make any sense as a warning. What you're looking at when you see this recession is a total bungling of the situation. Europe's economies needed stimulus + reform to maximize output and pay down debts. Instead they're getting reform backed with the lash of austerity, which is only burying them deeper in debt.Replace stimulus with higher nominal expectations and monetary support and I'm sold. The people who are overly focused on the level of indebtedness of the euro zone economies neglect the opposite side of the balance sheet, which is the expected future growth of nominal incomes.

Tim Duy on opportunistic disinflation by the Federal Reserve:

You see where I am going with this. The Fed was facing something higher than 2% inflation prior to the recession. Now they are looking at 2% inflation, which is also now the official target. It seems to me they might have used the recession to bring down the path of prices and along with it inflation expectations - something that might surprise the Fed's critics from both sides of the aisle.Bernanke has essentially chosen a new nominal growth path following the great recession, neglecting to provide monetary support for the period of "catch up" that has characterized past quick recoveries. Judging by the recent FOMC projection materials, Bernanke seems to believe that zone is between 4.3% and 4.6%. Looking at recently revised upward BEA release, RDGP increased 1.7% for 2011, combine that with a 2.5% increase in the price level, and you are left with a very rough estimate of 4.2% NGDP growth for the year. Still well below long term trend of 5%. Market projects of inflation over the next 30 years are still below 2 percent, which should give Bernanke plenty of reason to ease monetarily, but it appears as if he is content letting bygones be bygones.

No comments:

Post a Comment