Higher inflation would backfire by causing interest rates to rise. "You are not going to get any stimulus and you are going to make it much harder to restore price stability,"Volcker is implying that the higher interest rates that would accompany a higher inflation target would be contractionary. At first glance, his analysis appears correct, a higher interest rate would seem to suppress already weak aggregate demand. Yet with today's current low levels of inflation and interest rates at their lower bound, a higher interest rate stemming from a higher inflation target would be a by product of an improved economic outlook. To understand why this counter intuitive conclusion is correct, we need to look at David Glasner's recent research on deflationary expectations at the zero lower bound, my bold:

Thursday, March 22, 2012

If Only Bernanke Had Volcker's FOMC

Former FOMC president Volcker, like Bernanke, is overly reliant on the creditism view of monetary policy. Take this past week's comments at the Atlantic magazine news conference.

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

Debt for Lunch

Links from my lunch break:

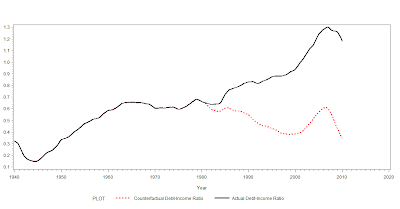

The debt-disinflation of the great moderation:

The debt-disinflation of the great moderation:

The 1980s, in particular, were a kind of slow-motion debt-deflation, or debt-disinflation; the entire growth in debt relative to earlier periods (17 percent of household income, compared with just 3 percent in the 1970s) is due to the slower growth in nominal income as a result of falling inflation. In other words, there is no reason to think that aggregate household borrowing behavior changed after 1980; indeed households rescued their borrowing in the face of higher interest rates just as one would expect rational agents to. The problem is that they didn’t, or couldn’t, reduce borrowing fast enough to make up for the fact that after the Volcker disinflation, leverage was no longer being eroded by rising prices. In this respect, the rise in debt-income ratios in the 1980s is parallel to that of 1929-1931.

Figure 2:

Think of it this way: If you borrow money and your income in dollars rises by 10 percent a year (3 percent real growth, say, and 7 percent inflation) then you will find it much easier to pay off the debt when it comes due. But if you borrow the same amount and your dollar income turns out to rise at only 4 percent a year (the same real growth but only 1 percent inflation) then the payment, when it comes due, will be a larger fraction of your income. That, not increased household spending, is why debt ratios rose in the 1980s.

Neither the 1980s nor the 1990s saw an increase in new household borrowing — on the contrary, the household sector in the aggregate showed a primary surplus in these decades, in contrast with the primary deficits of the postwar decades. So both the conservative theory explaining increased household borrowing in terms of shorter time horizons and a general lack of self-control, and the liberal theory explaining it in terms of efforts by those further down the income ladder to maintain consumption standards in the face of a falling share of income, need some rethinking.

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Krugman Again

I'm starting to think my co-worker (and loyal reader) Alexander just likes to link me Krugman articles for the sake of an argument when work is slow. The article in question today was Krugman's Sunday headliner comparing government spending during the "Morning in America" Reagan recovery and today's current recession. Krugman rightly points out that Reagan's government actually increased spending more than Obama's if state and local spending are included. What Krugman neglects to mention is that the majority of difference comes only AFTER the federal reserve turned on the monetary spigot, increasing NGDP growth to above 12% over the course of a single year. For comparison sake, here is the government spending graph that Krugman links to followed by NGDP and RGDP growth following both recessions.

Friday, March 2, 2012

The NGDP Effect of Devaluation or Why Exports Don't Matter

Lars Christensen effectively argues that during a currency devaluation,

the primary transmission mechanism for monetary policy has little to do with

restoring competitiveness, but instead works through the money supply on one hand and velocity on the other. In equation form, MV=PY=NGDP. The purpose therefore of

the currency devaluation in a depressed economy is not to increase competitiveness

in order to boost exports (although he concedes that it is one effect of the

devaluation) but to increase nominal spending through the expansion of the

money supply and increased velocity.

Lars provides the concise example of Argentina, who abandoned its dollar

peg in 2002, resulting in a rapid increase in the money supply, velocity, therefore

boosting NGDP and consequently real GDP.

While Argentina provides an informative example of the

benefits of devaluation on an economy in stagnation, I thought it would be important

to look at a country that used monetary policy to avoid crisis all

together. Poland, as shown by Marcus Nunes last February,

provides a unique example of the use of monetary policy to stabilize the broad

economy in a time of international economic malaise. Under normal circumstances, Poland’s

continued economic expansion would be of little note, but the world economies

since 2007 have been anything but normal. What makes Poland remarkable is that outside

of a minor decrease in RGDP growth in late Q4 2008 (-0.4%), the economy has

continued to expand at the same level as it did prior to Lehman’s demise. A close examination of Poland reveals that competitiveness

plays little importance in the transmission mechanism for monetary policy in maintaining Poland's impressive rise....

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)